Some want the British Raj back …

We, in India, don’t wish to become a clone.

Any one’s!

|

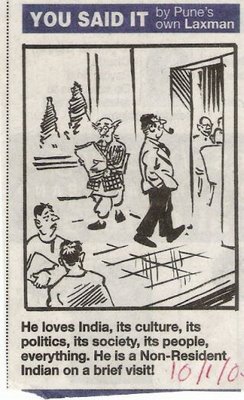

The two kinds of NRIs …

any centuries ago, a few foreign rulers (the Khiljis and Tughlaks) tried making India into a Persian-Turkic clone. They failed – miserably.

any centuries ago, a few foreign rulers (the Khiljis and Tughlaks) tried making India into a Persian-Turkic clone. They failed – miserably.

Then the English East India Company tried – and it got them the War of 1857. Queen Victoria tried – and it got her 90 years of violence, hartals, dharnas, strikes, et al.

All in all – a bad idea.

Who did this

The first thing that I did after reading this post below was to read the name of the author. To my horror, it was one Anand Giridhardas (AG).

I wonder what kind of education AG has had. Even if it was a lop-sided, ‘Anglo-Saxon is best’ kinda-American education, did he ever try and get his bearings right?

Is this what his history lessons were?

When empires wane, they live on, as the political scientist David Singh Grewal has argued, by embedding their values, systems and standards in a presumptive heir, as ancient Greece did through Rome and as Britain has done through the United States. Should it falter in due course, might America achieve the same through India — the preservation at least of the American idea and way of life?

That is implied in a cherished vision here — that if India does become as dynamic and powerful as China, then democracy, multiculturalism and the rule of law will continue to have a forceful champion, with or without America. (via India Has a Soft Spot for Bush – NYTimes.com).

I don’t know which part of the world AG comes from – but most NRIs, I know are rather touchy about their children getting to know something about India. One NRI father, I know, has decided that his daughter will be self taught – and not learn history, as it is taught in American schools.

But AG does not seem to have had that advantage.

Tracing the source of this nullah

I would be skeptical, of taking any kind of lessons (history or otherwise) from any who goes by the name of David Singh Grewal (DSG). The name itself is evidence of a badly mixed up mind (Note – Please see DSG’s comments below on his name) – which in bambaiyya language is called maraa-maree – a concoction of some fresh juices that cover up some stale or leftover juices.

AG’s guru, David (I am assuming, it is the same David Singh Grewal) says in another place

To be part of a particular global network, you have to adopt the underlying standard. This might mean learning to speak English, … or dressing in a suit and tie for a business meeting. If you do these things already – or if you are willing and able to change your behaviour now – the world may very well look flat. But if you don’t or can’t, you won’t see a level playing field at all; you’ll see distant fields on which others play. (ellipsis mine).

I am impressed. Such advice was earlier given free. But Bhai Dave ( In case he doesn’t want me to call him Bhai, I can call him Uncle Tom) seems to be making a living by charging money for handing out this maraa-maree – and couching it in good English and jargon. Such an activity is covered in the Indian Penal Code under Article 420!

Desi reactions to Western ‘perceptions’

The danger of taking lessons from any Punjabi /Saradarji who goes by the name of David is that they will never realize that India will make a bad clone.

Indian or an American

I have a question.

Is this the kind of wish that AG has for India (or any other country)? To be an Anglo-American clone?

I am unsure about quality of AG’s ideas or AG’s motivations. But he sure has used his ‘Indian-ness’ to get himself on a gravy train. All the while, downgrading the very gravy train that he is riding on.

Fortunately, for us, AGs wishes are irrelevant.

Advice … suggestions …

AG – If you are an ‘American’, I have a word of advice! Keep your Anglo-American-ness to yourself. We, in India don’t wish to become a clone – any one’s!

And if you count yourself as an Indian (never mind which passport you carry), you should press the “Empty Trash” button in your Mindbox. You will find that button in the Menu-> Files-> Settings-> Propaganda-> Received Trash-> Delete-> Empty Trash.

Caveat

This may look simple, but you have to do these delete actions, file by file. In some cases, these files have been received as virus files. These may have corrupted the Registry and finding the Rootkit is essential. In case the Rootkit itself is not deleted, it will keep creating new and freshly corrupted files. Of course, you have the option of formatting your hard disk! Any which way …

AG, you have a problem!

Related Articles

- The Remarkable Raj: Why Britain should be proud of its rule in India (indiatopics.wordpress.com)

- On the origins and rich history of Anglo-Indians (thehindu.com)

Exciting new series. From 1 Mar, 2010.

Exciting new series. From 1 Mar, 2010.

…but why the shock?

The core of any nation is its society – yet you cannot separate it from the polity.

India, when it was free, has always adapted and adopted to other cultures and peoples who migrated from other parts of the world. Yet, what kept India strong and free was its core ideas and a well defined coherent polity that embraced diversity.

Yet, after 1947, India “chose” to adopt a completely alien polity – abandoning the core values that had sustained it for the longest times.

People who did not embrace these alien ideas of political rule were mocked and described as anti-national and regressive…

…most intellectuals, especially the one’s trapped in the progressivist trap, have reveled in this “modern” experience and ignored the obvious weaknesses – considering India to be a work-in-progress…

…progress!

let’s move from the paradigm of work-in-progress towards working-towards-freedom.

Nation … polity .. society .. I am unsure what you mean and driving at.

Complex issue – which you are raising!

A decentralized Indian society, with shifting political borders but a strong ideological and belief structure is something that has been progressively diluted for now about 1200 years – from 800 AD.

Instead, Desert Bloc constructs like ‘nation’, ‘Empire’, ‘Sultanats’ have become a norm. China (and even India) are on the ‘nation’ trip – which possibly is in the short term an existential requirement to confront the Desert Bloc Asuric ‘enslavement’ polity.

As India recovers, (which will I think take time), this ‘nation’ concept will remain important. As it will in China. In such a situation, a strong centre will remain important for some time to come.

Yes … Armenians, Siddis, Jews, Chinese, Tibetans, Parsis … have all settled in India and some have done rather well.

What more can I say …

I think the last 150 (1857-2007) years of assault by the Western propaganda, cloaked under ‘progressive liberalism”. which you laid so well in this comment, created two difficulties. To oppose these Asuric political systems, one needed a certain measure of strength. In 1947, India had was in ICU. So, to move from ICU into a vibrant, free state that you wish for and aim towards was not an immediate possibility.

The three main challenges as I see during the post-colonial phase were – Education, land reform and putting the economy back on its feet. On Education we have done a real lousy job. We created a system which was ideal training a few lakh graduates to perfection for “acceptance” by the Western industrial system after the Indian tax payer was billed for many thousands of crores of rupees.

Land reform was tough one – and for each success we have also another failure. But this is something that is going to be tough. Unfortunately, the modern, industrial-military-BPO has re-invented the game of land grab. Industrials projects like Tata-Nano, Infosys-Wipro-Satyam have become huge real estate empires. The only real opposition to these projects has come from people Mamata Banerjee and Deve Gowda. The Marxists, Congress and BJP are the ones who are facilitating this modern land grab.

The third major one was the Indian economy. Here the successes have greater than failures. The biggest blot on this record is the sheer neglect of the SME sector – which has been joined by agriculture in the last 15 years.

So, any critique against the choices by the post-colonial India has be context based. At times I have sensed a non-contextual criticism, which to my mind, while valid, is irrelevant.

And still are …

I see your point when you say ““progressivism” always defers change for the future – thus preventing immediate challenges.

The debate, denial and disputing of milestones is also very much apart of the ‘progressivist’ trap – whereby a clique, which revels in these disputes, debates and denial wish to have a monopoly over the ‘progress’.

I agree with your response. I think my original comment was probably misplaced.

Your post makes some important points. On the subject of NRIs, wowever – it is important to note that there are two types of NRIs to consider in your critique.

1. NRIs who have represented themselves on their merit. Typically these would be the engineers, programmers, entrepreneurs, motel owners. Basically professionals or business related people who did not necessarily prescribe to any specific views in their profession.

2. NRIs in academics. A large number of Indian pHD students eventually decide to choose a career in academics. In this field as well there would be two categories: the Sciences and the liberal arts. While academics in general has complex dynamics, the sciences are a little more objective in the “promotion” of professors. It is the liberal arts where the mind control is the most and the “selection” of a candidate for a higher role – to become a voice – is based on subjective criteria – a pre-requisite would be progressive liberalism.

The so-called NRI voices you see in the media – are these selective voices. They are chosen to become voices primarily because they are designed to be the thought leaders to influence society.

It would be not only incorrect but also unfair to lump the category 1 NRIs with category 2B NRIs – who claim to represent the voice of the NRI.

Anuraag,

I know you are trying to use satire to make a broader critical point, but the way you do it here discredits the intelligence you bring to some of your other posts. Here’s why: criticizing someone’s name – whether Anand’s or mine – is not a good proxy for criticizing his arguments. Consider if I said, in relation to any of your posts on non-Indian subjects: “What could a guy with a name like Anuraag Sanghi possibly know about anything outside India?” and so on. That sort of view was only too common in the past, when racist/imperialist messages discredited voices based on their ethnic origin. Thank goodness we’re past that (to some extent) – and how sad that you’ve apparently bought into that racist worldview, but now from the opposite perspective.

As it turns out, my mother is a white American woman and my father is a Punjabi immigrant to the US. Which side of my family heritage do you think I should be embarrassed by, Anuraag? Which side should I disown to be considered a legitimate voice in your view? Is the the Punjabi side? The Anglo-American side? Would you take my arguments more seriously if my name were “all white” – e.g. David Smith, or “all Punjabi” – e.g. Gurbachan Singh Grewal?

How silly this all is… Look, I’ve written a book; it’s out with a new Preface for the Indian edition (it’s called Network Power) with Oxford University Press India. It costs 850 Rs. Since you are a successful IT person, you can probably afford this (admittedly high) price for the hard back. Read the book and criticize my arguments if you like. But don’t be so ignorant as to think that my name can serve as a proxy for my arguments – otherwise we fall back into that old world in which someone named “Anuraag Sanghi” would be dismissed as ignorant provincial for no other reason. In this case, of course, you’ve been acting exactly like an ignorant provincial. But it’s not because of your name – it’s because you’ve taken other people’s names as proxies for their arguments. The world is much more complex than that…

By the way, in my book, I do not assume that India will become a “clone” for US interests. The argument is significantly more subtle – though I’d like to note that carrying on this conversation in English over the internet is exactly the sort of dynamic of globalization that I discuss, and which I consider as a possible analogy to empire.

David – Firstly, I think an apology is in order. For the reason that my post borders (if not completely) on getting personal. Any further defence or explanation would only compound this lapse. I am grateful for your seeing it as a satirical tool, which it was meant to be!

Secondly, the post is not about your “name …as a proxy for my arguments”

It is about two things: – Is the Western-Anglo-Saxon ‘nation’ model at all appropriate for India – in fact any country, including the West. Its costs in terms bloodshed, war, genocide, to my mind, makes it completely unsuitable for humanity.

The lesser argument is that ‘Indians’ should know better! “Indians’ cannot become a part of the problem. Just like Haiti sparked the end of Spanish colonization, India initiated a greater demise of European colonization.

After such recent history (never mind the greater ancient history) for “Indians’ to promote a view which states

Or recommends that (AG’s fine English apart), that Indian become an American clone hurts!

Deeply!

Anuraag,

The point of the passage that you cite from my Guardian commentary is precisely to argue *against* the Thomas Friedman “world is flat” view now pervasive in the United States, and to focus attention on the inequities of the current global order. I may not have made myself clear enough in that piece. The point is that the world looks flat to folks who assume uncritically that there is no power involved in the construction of a global regime that takes it as obvious and uncontestable that Anglo-American norms (including communicating in English, as we are doing) are the obvious standards by which globalization should proceed. The point of the passage–which, again, may not have been clear enough–and certainly of the book I’ve just published is precisely to offer a criticism of Anglo-American-led globalization, and to think about how national polities (including India) can resist the ways in which globalization is coercive. Does the world look “flat” from the perspective of the dominant network–e.g. English-speaking, technologically plugged-in, etc.? Perhaps – but it’s an illusion that such an experience is universal. Others see huge gaps, exclusions, barriers, and rightly so.

I do not speak for Anand Giridharadas or what he (or anyone else) took from my book, but I certainly do not think India should or could become a clone of the US. (For what it’s worth, I don’t think Anand does either.) Just as you say, that is not even possible, even if it were desirable – which it obviously is not. What concerns me is the way that power works in “non-political” ways–through culture, economics, and technology–to impose a global regime that is similar, in some respects, to past instances of more obviously “political” imperialism. On this view, Indians can become caught up in the “network power” of the United States, even without being subjected to explicit domination.

In the introduction to the Indian edition of Network Power, I describe some of the ways in which India is, in fact, comparatively privileged in a global order of Anglo-American creation – since many Indians are relatively more “plugged in” to dominant linguistic, technological and cultural networks in ways that others folks in the developing world are not. It is imperative that citizens of India — and of China, Brazil, Indonesia, and other rising developing powers — think about what sort of world they want to build as they develop the power to reimagine the current global order. It is not too early to do this, nor should it be thought that because a country was once the victim of foreign domination that it is immune from needing to be self-critical or on guard against dominating tendencies. (Here, it is China’s current role, e.g. in the Sudan crisis, that I am thinking about, rather than any Indian foreign policy.) More broadly, it seems to me that, just as you say, India needs to support an alternative world order to the one now in place, and it also seems to me that India will be the most well situated country to do that, since it is uniquely tied to the currently dominant global networks but also to its own sources of critique and creativity.

I am not sure how much of this you’d disagree with – but my argument in the book stems from an effort to build bridges and conceive global alternatives, while focusing critical attention on the way that power works in the construction of the current global order. If you send me your e-mail address, I will send along the Preface to the Indian edition of the book (unless you fancy getting the hardback).

Coercive in subtle and not so subtle manners. Yes. Resisted is too weak a thing to do!

Rejected, trashed – to my mind is the correct thing to do.

Thank you so much!

Since it is the season for ‘heritage’ – about 2 centuries back I was Punjabi. For the last 200 centuries I have been in South India. The one thing I like about Punjabi thinking is their willingness to cut out the subtleties and look at the मोटी बात. The South Indian trick is always (as my father puts it) simply to resort to removing बाल की खाल.

Now I can switch between these two – or at least I flatter myself, that I can.

Now read this passage, and mind you, it is not a small phrase or a clause, but a complete, standalone idea that AG is promoting. He has august company with people like Krittvas from Reuters who alleged that Indian money lenders were accepting borrowers wives /daughters as collateral security or Andy Mukherjee who wants India to bang a begging bowl in front of Unca Sam!

Now please read this passage!

When empires wane, they live on, as the political scientist David Singh Grewal has argued, by embedding their values, systems and standards in a presumptive heir, as ancient Greece did through Rome and as Britain has done through the United States. Should it falter in due course, might America achieve the same through India — the preservation at least of the American idea and way of life?

That is implied in a cherished vision here — that if India does become as dynamic and powerful as China, then democracy, multiculturalism and the rule of law will continue to have a forceful champion, with or without America.

To my ‘provincial’ mind’ (aka मोटी और मंद बुद्धि) the takeaway is India should become a US clone – and everything that the US represents is good and great – and Indians should just stop protesting, curl up and accept ‘it.’

Proof of your hypotheses?

Read this by Ananya Vajpeyi – who gets carried away by what a hack, well trained in using polished English, proposes.

Very well said and very right too! About time too!

Anuraag,

Again, Anand’s (or anyone else’s) understanding of these issues is something he (or they) would have to speak for. I cannot. But it doesn’t seem to me that claiming India is the best situated rising power to speak up for democracy, human rights, and multiculturalism means India must be understood as a US clone (or clone of any other country). No doubt India will (and, I think, should) promote these values in expressions that reflect its own history and cultures, but also make them available as constituents for a reformed world order. Doing so will be a diplomatic, political, and spiritual challenge for 21st century Indians.

As to my argument about network power, may I suggest that this conversation – carried on in English, and over the internet – is exactly an example? On the one hand, it’s terrific that we’re able to connect through global linguistic and technological networks. On the other, it represents an enormous exclusion in that many people in India (and the US and elsewhere) cannot do so – and thus, to my mind, any celebratory view of globalization needs to be tempered by a concern for those excluded from global networks – as well as for the concern that we maintain a diversity of standards in some cases (rather than simply switching on to the Anglo-American standards, as seems to be occurring.) Again, this is something that I cannot express here with the same precision that I do in my book.

My book was recently reviewed in The Hindu (a few days back) but alas that reviewer did not understand my argument. Here is a review (from the FT) in which the reviewer did understand my argument, and he expresses a lot of it very well and concisely – though he and I are, in fact, on different sides of the political spectrum. I am pasting it here for your consideration – it is the sort of dynamic described here that I think is tantamount to “non-political” forms of power that can be exercised globally.

http://us.ft.com/ftgateway/superpage.ft?news_id=fto052320081343411263&page=1

By the way, I know you are again being satirical, but my saying you were provincial was *not* a general comment but a criticism of how you were behaving in your original post, where I was called a Punjabi “Uncle Tom.” Since you have apologized for that, I withdraw the comment entirely. There is, of course, nothing provincial about a cross-continental conversation about alternative geopolitical futures.

Anuraag – I apologize for butting in your discussion – but I thought I would add my own 2 cents worth 🙂

David – From what I can tell, the summary of the message of your book in the Financial Times was that Globalization has its network power, where “dissent is possible, but pointless.”

Assuming that your book views “network power” in dim light, I can see that you represent a side of the argument which opposes globalization. I suppose you sympathize with the population of the world, because it presents them with a Hobson’s choice.

I think, both sides of the argument have been articulated for decades, if not for a couple of hundred years, in various forms. The labels have changed, but the arguments have not.

These two sides of the argument (what FT says and what I assume you are saying) represent a one-dimensional view of the problem – left vs. right (capitalism vs. Marxism or shades thereof).

I would argue that the core “problem” is not “globalization,” or “trade” but the “management” of trade.

The world has traded for thousands of years and “globalization” is not a modern phenomenon. What changed in “modern” times – was when trade negotiations lost their freedom to the state. State sanctioned monopolies (such as the East India Companies – English or Dutch) became proxies for a few families and states and their military force. “Trading” ships were more about plunder and loot and a culture of “vrijbuiter,” meaning “free booty” that could be collected in the open seas.

These, state sanctioned monopolies destroyed the free trade and the free markets around the world – especially in India and other parts of Asia.

Even post-mercantile capitalism, as is popularly believed, should in theory, support “free markets,” however, as Raghuram Rajan argues, in “Saving Capitalism from the Capitalist…” that the capitalists actually use the power of the state to protect their economic power through lobbying – for which he provides several modern examples. These are not too different from the several laws that the English “merchants” lobbied the Parliament to pass to exert control over the “employee weavers.” These include the Bugging Act of 1749, the Worsted Act of 1777 and the Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800. These would make it legal to publicly whip or hang workers (in England) if they failed to meet quality or keep deadlines. Certainly had little to do with “free” markets.

Another implicit argument, you are making above, is that the English language, has become such “network power,” pointing out the fact that this discussion is taking place in English. FT seems to agree with your premise, saying that “Since English has become the first global lingua franca, many non-native speakers have freely chosen to speak it.” As Anuraag and I have discussed in some previous posts, the rise of English, and its present sustenance, has little to do with the power of the network, but about the power of the state.

In India for example, the Indian State has sustained the monopoly of the English language in higher education. In India, even today, English is a state subsidized language, at the cost of other languages. Without this prop, there is plenty of evidence that English will lose it eminence – and will exist – but only at the margins – like Farsi (I don’t mean Urdu or Arabic), during the Islamic rule.

Indic polity had established a framework that ensured political, economic and personal freedom to the nation (the triad of freedom). It allowed the Indian nation to prosper without ever threatening the diversity (and I sincerely hope that you don’t believe what they teach you in Harvard, that India was not a nation until the 20th century 🙂

I would strongly urge you to look orthogonal to the one-dimensional (left vs. right) view that remains in focus in all arguments in western intellectual thought. I would urge you consider that this debate that is trapped in a certainly time-line or “modern” as you would imagine… consider the possibility that these arguments have existed in the pre-European world – and in fact were premised in providing the triad of freedom.

The mere fact that you have a part-Indian ancestry might encourage you to understand, why Indic polity represented and cherished freedom, unlike paradigm of the “left vs. right.”

I would encourage you to read my upcoming book titled, “Tatya Tope’s Operation Red Lotus : The story the Anglo-Indian War of 1857” While the focus of the book is the War of 1857, that has been wished away as a “mutiny” in the past, represented a war between the Indian nation and England – and at the core of the War was Indian leadership, that represented India’s obsession for political, economic and personal freedom. The book will be published by Rupa and Co., in India in the couple of months.

Dear Parag,

Your book on the history of 1857 sounds very interesting. Why not write up an account of what you call the “triad of freedom”? It sounds like it deserves an independent account as to what it is and how it presents an alternative for political reform today.

Two quick things – the FT review may have characterized my book as suggesting dissent is possible but pointless, but I don’t actually argue that exactly. I argue that in many cases, it is possible but pointless for individuals *as individuals* to resist forms of network power, and that what is required is collective action of various kinds. The book is now out from Oxford Press India, so if you have a chance, take a look at a copy. I do try to move beyond a strict left/right dichotomy but how one succeeds in such arguments is ultimately for readers and not for the author to decide.

I agree entirely that the problem is how to manage trade to best fulfill the conditions of human flourishing rather than to use it (as you suggest) on behalf of state monopolies or, I might add, in keeping with the general libertarian notion that the market always delivers good outcomes. To the extent you seem to edge toward that latter view in your remark – defending free trade in itself – I’d suggest that we never saw free trade in the past but we shouldn’t want to see it now either, since the market does not itself deliver outcomes that are normatively desirable (except, again, on the libertarian view). Markets have always been managed by politics, which is a good thing – depending on the political set-up, of course. My dissertation is on the history of economic thought, and I have a couple early chapters on trade in the ancient world (mainly Greece and Rome, but with some limited discussion of the Near East and India). I don’t think it will be published for a few years, alas, but this is something I am interested in.

As for whether India was a nation before the 20th C., of course it was (in the sense of the peoples within the chardham, who had a collective sense of identity) but of course it wasn’t a nation-state (because it was not politically independent). Before colonization, of course, it was an independent political entity, unified to a greater or lesser degree under various empires – but this is something I alas know little about!

By the way, I have just published an essay on current globalization in the issue for this month (Sept) of Seminar. It’s called “What Keynes Warned about Globalization.” With your interest in trade, you may want to look at it. I am afraid it is not yet online but will be in a month. (I think Seminar posts its stuff for free only after the current issue is off the newsstands.)

Dear David,

>>>”I argue that in many cases, it is possible but pointless for individuals *as individuals* to resist forms of network power, and that what is required is collective action of various kinds.”

However, will you not hit the same brick wall that has been endlessly discussed in western discourse? the debate of the “collective” vs. the “individual?” I would argue that the answer is orthogonal to this one dimensional axis.

>>”whether India was a nation before the 20th C., of course it was (in the sense of the peoples within the chardham, who had a collective sense of identity)”

You are right that India was never really one state – but it was always a nation. However, I would disagree with the statement that it was a “collective sense of identity.” It was in reality an adherence to a polity at several levels. This polity ensured the triad of freedom, by limiting political and economic power of the administrative functions of the local states. A ruler who adhered to this polity was respected one who did not was not. The Indian epics and the so-called Indian mythology are all about protecting and defending this polity, and recognizing those who did. In fact these stories and the design prevented the Indian nation from ever becoming a mega-state.

>>>”I’d suggest that we never saw free trade in the past…”

This is exactly what I am trying to counter. As long as you look to history where nations were states, you will not see “free markets.” Whenever either of the three – political power, economic power or theosophical power collaborated or colluded with one or more of the other – with the idea of forming a “state,” the markets would be “managed.” Which is what you will always find consistently in middle eastern or western history.

That is is why I would encourage you look beyond what you are “told” about Indian history – and see how Indic polity was able to solve what the libertarians in the US have been unable to.

>>”…the problem is how to manage trade…”

Managing trade is not a solution – but the core of the problem… in western history – trade was *always* managed… either directly by the state (communism) or indirectly by the state (crony-capitalism and all shades thereof – which is what western economic thought is largely about). I say that “managed trade” is at the root of the problem… because there is no such thing as a “benevolent trade manager.”

When you say “economic thought” – it important to realize that it simply represents one of the three important pillars on which freedom rests. Learning from the experiences of Europe, the US constitution separated the “church” from the “state” – which is an attempt to separate the “political” power from the “theosophic” power; however, they were unable to separate economic power from the state. In fact, foreign policy even during 1790s was largely dictated by trade. The final nail in the coffin was the creation of the federal reserve in 1913, which was the perfect (yet grotesque) marriage of economic and political power.

While some libertarian minded people are attempting to separate these, the libertarians do not really have a road map of how and where to go with this…

…the west has never witnessed this in their history. What libertarians describe as “Austrian Economics” was never a “real” model. To find any real solutions, they will have to look east – and specifically India – to the period when it defined its own polity. Not “modern” India however, which is perhaps a Frankenstinian combination of western crony-capitalism mixed in with western marxo-communism. There is nothing *Indic* about modern Indian polity.

About the “triad of freedom” – you can send me an email at paragtope at gmail dot com – and I can send you the introduction of my book – which discusses some of these ideas. In the introduction, I refer to a five point Proclamation of Freedom made by the Indian leaders of the War of 1857. It indicted the English rule for its oppressiveness in these three areas of freedom and presented a road map to go forward.

That is perhaps – what the world needs even today!

I would simplify the development of the four Western political systems – i.e. Feudalism, Capitalism, Socialism and Communism, to two things.

Property and slavery – the two elephants in the room of Western history.

Feudalism

Apart from the King and his Nobles, 99% of the people were

1. Slaves (humans who could be bought or sold)

2. Serfs (humans whose labour could be bought or sold)

3. Tenants (humans, who had to ‘voluntarily’ pay rent, taxes, tithe, customs, excise to retain their output, labour and freedom).

Primogeniture ensured that the State had enough people, who: –

1. Were unemployed to fill up armies,

2. Could be ‘broken’ into the system to serve ‘noble’ causes,

3. Could be incentivized with grants and lands,

4. Could be tutored into religious and political propaganda.

As the feudal population grew, larger armies enabled foreign invasions – initially by the Spanish and the Portuguese. Loot from the New World created a new set of monsters – and instead of becoming slaves (by Islamic enslavers like Barbarossa), the West starting enslaving.

Within a century, the Christian West replaced the Islamic Arabs as the ‘market leaders’ in enslavement. The genocide of the Native Americans, started by the Spanish in the 16th century was completed by the Anglo-Saxon Bloc by end-19th century.

As Native American populations reduced, Africans were imported. One of the most populous land masses of the world, was used a ‘resource’ to fuel the rise of Capitalism.

Capitalism

Was about the ‘productive’ use of loot. Fuelled by, possibly, the world’s largest ever ‘transfer’ of wealth – from the Americas to the Europe, and combined with slavery, saw the rise of Europe as power. Western ‘learning’, ‘innovation’, ‘renaissance’ and ‘enlightenment’ were all fuelled by loot and slavery.

Property remained the prerogative of the few. Property rights spread to the capitalists – but still remained elusive to the ‘commoners’ till the nineteenth century.

Capitalists wanted and got ‘laissez faire’ capitalism – which was a ‘coda’ for unlimited slavery. And not as votary for ‘free’ markets. Remember, the Magna Carta, The Church all sanctioned slavery.

Socialism

Combine slave revolts, with poverty of the White populations (due to low wages a result of cheap slave labour) and increasing urban population (due to the better nourishment fuelled by loot and slaves). And we soon see the birth of ‘organized’ labour. Capitalism, faced with decreasing availability of labour and loot, resorted to ‘protectionism’.

Justifications to rig the market, (usually referred to as Ideology) on behalf of the few capitalists was built up. The property-less were given some property rights. New laws for ‘labour welfare’ were invented as, One – barriers to entry for new capitalists, and Two – to assuage ‘organized’ labour. The State, earlier the tool for exploitation, was given a new avataar – and became the Protector-Benefactor.

Communism

Karl Marx and Engels filled a void of a nervous Europe, between 1830-1870, after on-shore slavery became a impossibility. Slave revolts in the Haiti, Caribbean, and South America made enslavement a no-go.

Communism proposed that the State become a benign, monopoly slave owner – unlike the ‘exploitative’ and ‘extractive’ Capitalist. Communism found traction in all those ‘nations’ which did not dilute Capitalism /Feudalism with Socialism.

Western history covers the elephants in the history room – the elephants of loot and slavery, with red herrings of ‘innovation’, ‘reform’, ‘technology’ et al.

In spite of separating the Church and the State in the US, how many Catholics have become Presidents in the last 225 years? All that this ‘separation’ achieved was that the ‘politicians’ did not have to share power with the religious authority of an independent and demanding Vatican – which was replaced by fractious and collusive Protestant factions.

Now compare

Is there an Indic political system at all?

India, till the 12fth century (advent of the Islamic iqtedari system) vested property rights with the producer. Slavery (distinguished by capture and recapture, buying and selling, state protection, ‘free’ markets) were unknown in Indic regions.

Completely ignored by ‘modern’ Western education system, (which India also blindly follows), the Indian political theory and its application have been largely forgotten in India too. Simple leads …

1. What is Sanskritic word for slave? Or what does the Indian narrative call Slave owners?

2. Why do traditional traders resist taxes even today? The biggest tax offenders of modern India are the traditional ‘marwari’ business man. Why?

3. What triggered the persecution of the Roma Gypsies in Europe?

4. How did the Roma Gypsies start the Church Reformation in Europe?

5. Why does India have the lowest crime rates and incarceration rates in the world? Yet was behind the biggest crime wave in history?

6. Why and how did India build the world’s largest private reserves of gold? Without loot, luck or slaves?

7. From the carbon-dated 3000 BC Indus Valley to the India in 2000 AD, how could India resist cultural and military invasions?

8. How did India emerge as software service economy in a short 15 years?

9. India is today a counterpoint in softpower – in TV, cinema,publishing, newspapers, et al! How come?

10. While the Western world is going public sector, how come India continues down the private sector path?

There is a lot to what you both say, but I fear it requires something I find untenable: the assumption of a “golden age” – and, strangely to my view – the assumption that such a golden age justifies a sort of anarcho-libertarian fantasy of business without government interference.

The world we are in is no doubt a broken, sad, wounded world, with hope and despair vying in equal parts in our imaginations. It is a world of terrible twisted histories to which we are all heir. But it is the only world we have, and we must inhabit this world – not a world of our fancy – before we hope to make any other.

This is the starting point for the kind of clear-eyed, critical analysis that I think we need, which will not seek historical comforts for present maladies, but will examine the past, present, and future with sobriety and humility.

Now, I fear I must stop posting on this blog – enjoyable though the conversation has been – for I have a looming deadline in two weeks and must get back to work! With best wishes –

>>>but I fear it requires something I find untenable…

no surprise there 🙂

Looking forward to Parag’s book too…should be whiff of fresh air after years of romilathaparisms.

BTW, what about the treatment of the dalits?.How does that fit into Indic culture?

Dalit mistreatment doesnt seem much different than slavery/treatment of the Romas to me.I have not read Anuraag’s take on it either in any of his posts.

Kindly address this issue.

>>BTW, what about the treatment of the dalits?.How does that fit into Indic culture?

Indic polity was *all* about freedom from the three administrative functions who had potential to accumulate and abuse power (political, economic, personal).

While some breakdown in polity started in the north a thousand years ago, it was the 19th century that witnessed the total eclipse. Not only did Indic polity completely collapse, the ideas within its framework were turned upside down by those who became entrenched with new found power. For example, land ownership laws that protected the economic interests of the manufacturers remained in existence until India witnessed the biggest land grab in its history, in the nineteenth century.

In one of “background” chapters of Operation Red Lotus, there is an example of how weavers lost their negotiating power with the arrival of EEIC licensed merchants. Pre-EEIC, a weaver would accept a textile order upon the receipt of a deposit from the merchant. The weaver’s negotiating power is evident in the fact that he could cancel the contract, if prices fluctuated, by returning the deposit. The merchants, like the weavers, were fragmented and had no collective power (which was the basis of Indic polity). This changed when the merchants became EEIC license holders – with the backing of the state to force negotiation of better terms. What was once a “deposit”, became an interest bearing “loan.”

You can extrapolate the rest of the decline. Your observations about the recent state of India’s economic structure are accurate, however, you are projecting them into the past incorrectly.

The progressive-liberal paradigm expressed in India’s post-colonial constitution has created a diversion that prevents India from looking inward for sustainable solutions.